By Adv. Shriya Maini.

First Part of this Series, can be accessed here.

- Exclusion in Emergency: Hurry versus Hearing

Whether it is for public safety, public interest, public health or public morality- the action, preventive or remedial, that is needed, is the requirement of notice and where a hearing may be obviated, would be exceptional cases of Emergency. The reasoning here is that a plausible hearing could delay the Administrative Action, thereby defeating the very purpose for which it was constituted. But if the right to be heard was to paralyze the process, the law would inevitably exclude it. Hence, if to condemn unheard is wrong, it is wrong except where it is overborne by dire social necessity. Therefore, examples such as where a dangerous building is to be demolished, or a company has to be wound up to save depositors, or there is imminent danger to peace, or a trade dangerous to society is to be prohibited, dire social necessity requires exclusion of the elaborate process of fair hearing. In the same manner, where power theft was detected by officials, immediate disconnection of supply was said to be non-violative of the Principles of Natural Justice.

One of the most controversial examples here would be that of preventive detention, where the detenu is not given an opportunity of hearing before being detained, as in the case of Sadhu Singh v. Delhi Administration. Another point to be kept in mind here is that the action taken is primarily temporary in an emergent and immediate situation, overlapping with the area of excluding audi alterum partem, due to interim preventive action.

A very fundamental question that arises here is what circumstance is really so dire, urgent, critical, burning, insistent, beseeching and demanding for it to be categorized as an “emergency”, granting an exclusion of Principles of Natural Justice, and if it is, then to what extent?

Cases like Ashwini Kumar v. State of Bihar stand testimony to the factum that a hearing may be prevented if it defeats or abrogates the very purpose/object of the action being taken. Under the garb of securing Indian Defense, countering terrorism by giving overriding considerations in national security may be categorized as cogent enough reason to exclude Principles of Natural Justice.

No doubt, Natural Justice is pragmatically flexible and is amenable to capsulation under compulsive pressure of circumstances and the same has been observed by the Apex Court time and again. It has been said that “Natural Justice must be confined within its proper limits and must not be allowed to run wild. The concept of Natural Justice is a magnificent thoroughbred on which this nation gallops forward towards its proclaimed and destined goal of justice, social, economic and political. This thoroughbred must not be allowed to run into a wild unruly horse, careering off where it lists, unsaddling its rider and bursting into a field where the sign “no pasaran” is put up”.

Gradually though, the judicial attitude has turned austere in matters of accepting the argument of the need of quick action, to deny a hearing or fairness in procedure to an affected party. The Apex court has kept a vigilant and watchful eye on the prime question of excluding hearing in the name of urgency. In simpler terms, it has shown a stark tendency of not readily accepting lightly, the argument of “urgency” so as to exclude the fundamental divine laws of Natural Justice. The foremost reason for this appears to be the categorization of the degrees of urgency wherein only cases of extreme urgency ought to be given the special status of exclusion. The Test is to strike a balance between the competing claims of hurry and hearing in the contextual backdrop of facts and circumstances of a particular case. Before accepting an argument contending exclusion of Natural Justice in a given situation, all possible efforts to salvage this cardinal principle to the extent possible should be made by the adjudicating authorities, as highlighted in Swadeshi Cotton Mills v. Union of India.

The concept of post-decisional hearing was highlighted with relevance to administrative and judicial gentlemanliness especially in a situation of emergency wherein the precious rights of people were involved. However, the administrative determination of an emergency situation calling for the exclusion of rules of Natural Justice was not final but subject to Judicial Review. In Swadeshi Cotton Mills v. Union of India, the Apex Court held that the word “immediate” in Section l8-AA of the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act cannot stand in the way of the application of the rules of Natural Justice. Under Section 18-A of the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act, the Central Government could take over an industry after investigation, but under Section 18-AA(l) the government can take over without any notice and hearing, on the ground that production had been or was likely to be affected, and hence, immediate action was necessary. The question was whether Section 18-AA(1) excluded the Principles of Natural Justice. The government took the plea that since Section 18-AA(l) related to emergent situations, the Principles of Natural Justice were bound to be excluded. Furthermore, it was also argued that since Section 18-A provided for hearing and Section l8-AA(l) did not, consequently, the Parliament had excluded a hearing therein. Rejecting all those arguments, the Court held that even in emergent situations the competing claims of ‘hurry and hearing’ were to be reconciled and that the application of the audi alteram partem rule at pre-decisional stage may be ‘a short measure of fair hearing adjusted, attuned and tailored to the exigency of the situation’.

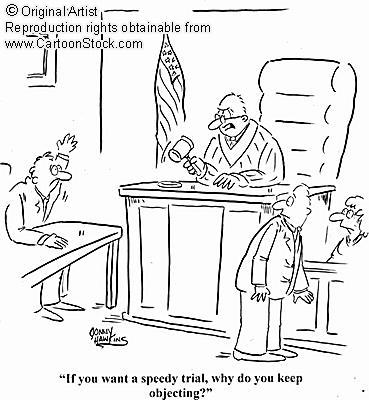

In the case of Mohinder Singh Gill v. Chief Election Commissioner, the question was, whether the Election Commission was bound to hear the candidates before countermanding the polling in a constituency to order a fresh poll, because of hooliganism and breakdown of law in order at the time of counting of votes. Discounting the Petitioner’s contention of speedy justice to exclude Natural Justice, the Court held that speedy decisions can never completely exclude compliance of Principles of Natural Justice, but could merely modify their applicability in a particular situation. The Apex Court emphatically remarked that: “… Cardinal Principles of Natural Justice as a condition precedent for decision making cannot be martyred for the cause of administrative immediacy, unless the clearest case of public injury flowing from the least delay is self-evident. Not exclusion but only contraction, granting post decisional opportunity, trial-type trappings or slight situational modifications maybe tailor made in the Natural Justice procedure”.

- Exclusion in Cases of Confidentiality:

Another interesting area where a plausible escape route from the Principles of Natural Justice may be found, is that of “Confidentiality”. L.J. Simon Brown puts it forth beautifully, when he says “what is really required is a balance to be drawn between the need for confidentiality and disclosure”.

In Malak Singh v. State of Punjab, the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India categorically held that the maintenance of a surveillance register by the police is a “confidential document” and neither the person whose name is entered in the register nor any other member of the public can have access to it. Furthermore, the Court ascertained that if the Principles of Natural Justice were to be observed in a situation, it may defeat the very purpose of surveillance and that there is every staunch possibility of the ends of justice being defeated instead of being served. The same principle was followed in S.P. Gupta v. Union of India, where the Hon’ble Supreme Court held, that no opportunity of being heard can be given to an Additional Judge of a High Court before his name is dropped from being confirmed.

Since, the climate of opinion has changed and the administrative process has become fairly translucent today, even though the discretion is granted to authorities to exclude an opportunity of hearing, sufficient and relevant grounds for the same must be given before such powers are exercised. However, it must be highlighted that in a democracy like India, such surveillance may provide a very serious constraint on the freedom and liberty of the people, and therefore, critics maintain that a surveillance register cannot be so drastically and utterly administrative and non-judicial, that it is difficult to envisage the mandatory application of the Rules of Natural Justice.

- Exclusion in Case of Purely Administrative Matters:

Administrative and Policy decisions, by virtue of their very nature of being non-judicial, attract exemption from Principles of Natural Justice. For students of law, this is an area of particular interest and concern, since one of the foremost examples of an administrative decision is that of academic evaluation. Prima facie, academic adjudication by way of cogently correct and true assessment of performance of a student via an examination negates any right to an opportunity to be heard. However, in the presence of alleged bias or malafide, the Courts have been found to interfere.

The Supreme Court in Jawaharlal Nehru University v. B. S., held that the very nature of academic adjudication appears to negate any right of an opportunity to be heard. A student of the University was removed from the rolls for unsatisfactory academic performance without being given any pre-decisional hearing. Therefore, if the competent academic authorities examine and assess the work of a student over a period of time and declare his work unsatisfactory, the rules of Natural Justice may be excluded.

In the same manner, in Karnataka Public Service Commission v. B.M. Vijay Sharma, when the Commission cancelled the examination of the candidate because, in violation of the rules, the candidate wrote his roll number on every page of the answer-sheet. The Supreme Court held that the Principles of Natural Justice were not attracted observing that the rule of hearing must be strictly construed in academic discipline and if this was ignored, it would not only be against the public interest but would also erode the social sense of fairness. However, this exclusion would not apply in case of disciplinary regulatory matters or where the academic body performs non-academic functions. Granting sanction of prosecution is a purely administrative function, and therefore, the Principles of Natural Justice are not attracted.

Part III of the series can be accessed here.

To be contd.

Note: The link to the preceding part has been placed at the beginning of this post and to the succeeding parts of this series will be placed here, as and when they are published.

About the Author

Advocate Shriya Maini is a young, bright, scholarly, advocate turned entrepreneur, currently practicing at the Supreme Court of India, the Delhi High Court and the District Courts at New Delhi. She specializes in dispute resolution and as an unabashed feminist, particularly enjoys criminal litigation. She is a graduate of Gujarat National Law University, India who then pursued the Bachelor of Civil Laws Programme on a full scholarship (Dr. Mrs Ambruti Salve Scholarship) sponsored by Dr. Harish Salve, Senior Advocate, from the University of Oxford, specializing in International Crime. As a recipient of the Oxford Global Justice Award 2015 for Public International Law, she assisted the President of the International Residual Mechanism for the Criminal Tribunals (MICT) at The Hague, Netherlands. She is now back in the Courts of New Delhi, India to pursue her passion in litigation. Additionally, she has recently been appointed as a Visiting Professor for International Criminal Law at National Law University, Delhi, India.

Advocate Shriya Maini is a young, bright, scholarly, advocate turned entrepreneur, currently practicing at the Supreme Court of India, the Delhi High Court and the District Courts at New Delhi. She specializes in dispute resolution and as an unabashed feminist, particularly enjoys criminal litigation. She is a graduate of Gujarat National Law University, India who then pursued the Bachelor of Civil Laws Programme on a full scholarship (Dr. Mrs Ambruti Salve Scholarship) sponsored by Dr. Harish Salve, Senior Advocate, from the University of Oxford, specializing in International Crime. As a recipient of the Oxford Global Justice Award 2015 for Public International Law, she assisted the President of the International Residual Mechanism for the Criminal Tribunals (MICT) at The Hague, Netherlands. She is now back in the Courts of New Delhi, India to pursue her passion in litigation. Additionally, she has recently been appointed as a Visiting Professor for International Criminal Law at National Law University, Delhi, India.

Comments

One response to “Exceptions to Principles of Natural Justice: Part II”

[…] https://www.lexquest.in/exceptions-to-principles-of-natural-justice-part-ii/ […]