By Adv. Shriya Maini and Ms Chethana Venkatraghavan

This write-up is for those students who have realized that they have a law exam tomorrow and are looking for a source which discusses the practical and theoretical aspects of law in a deliberately simple form. This is also for those lawyers who are struggling to fill the gaps between the books of procedure and the law in practice. We write about what we have learnt through our trials and errors. Unlike other websites, we hope to engage you at multiple levels – the theoretical aspect of the law which we learn as students and the practical approach of law which only an Attorney at Law can provide.

How the Get-Out-Of-Jail-Card Functions in Reality

This is the first part of a two-part series on all you need to know about Bails and Anticipatory Bails. As people who have been through the mind numbing exercise of reading unnecessarily complicated sentences to gain a basic understanding of a rudimentary aspect of procedural law, we hope to simplify it for you. You will find videos, images, tables and flow charts that explain the concept in a manner that saves you time and effort to pursue other lawyerly passions like finishing an entire season of a TV show in a week.

Sections in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 that are discussed:

| Section 2(a) | Defines bailable and non-bailable offences |

| Section 437 | Regular Bail application |

| Section 438 | Anticipatory Bail application |

| Section 439 | Special Powers of the Sessions Court and High Court regarding bail |

The terms ‘bail’ and ‘anticipatory bail’ are widely used in criminal law, and one reads about them in the papers frequently. The concept of bail is a fascinating phenomenon and for those not well versed with the intricacies of law, it may seem as easy as walking up to the Police, demanding bail, paying money and walking away, scot free!

However, the reality cannot be further from this perception, as bail is a complex process that has a lot of conditions and precursors before it is actually granted. This article will be about securing bail and anticipatory bail for your client and it will go further than the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 (“CrPC”) and give you a glimpse into an Attorney’s approach to securing bail for the accused.

What is the purpose of bail?

The purpose of bail is to ensure an accused’s presence in court, as and when required. A bail is essentially a written agreement between the accused and Court to the effect that the accused agrees that s/he would appear in court and assist, cooperate with the investigating authorities (the police) as and when called upon by the Court.

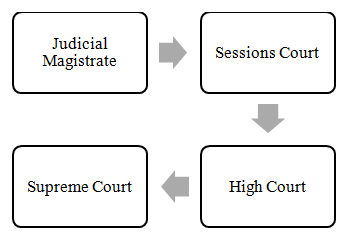

Before we look at the concept of bails in detail, let us look at the various judicial authorities involved and the hierarchy of judicial authorities with respect to bail applications. Bail applications are usually filed first before the Hon’ble Judicial Magistrate’s Court (depending upon the gravity of offence and nature of punishment, one may have to file before the Sessions Court). If the bail application is rejected by the Magistrate’s Court, the accused has an option to approach the Sessions Court, the High Court and then the Supreme Court.

Before we discuss this further, there are two important terminologies which are unfortunately misused and sometimes interchangeably used in common parlance – police custody and judicial custody.

What is Police Custody and Judicial Custody?

When an FIR has been lodged against the accused by the Police and s/he is arrested by the Police for the purposes of investigation, s/he must be produced before the local magistrate within the next 24 hours. Upon the discretion of the Magistrate, the accused is sent to Police custody or Judicial Custody. Police Custody (police remand) essentially means that the accused has been arrested for investigation which includes questioning, visiting the spot of incident, admidst all other formalities. Once the investigation is completed by the police, the Investigating Officer submits before Court that s/he no more requires police custody of the accused thereby implying that the accused may now be sent to Judicial Custody. Once in Judicial Custody, the accused has to be produced in Court after the expiry of every 14 days. Judicial custody means that the accused is now under the judicial authority’s control (this means the Magistrate or Sessions court) unless the Judge orders that the Police re-take custody of the accused owing to new developments in the case or other exigent circumstances.

What is the difference between Bails and Anticipatory Bails?

Bails

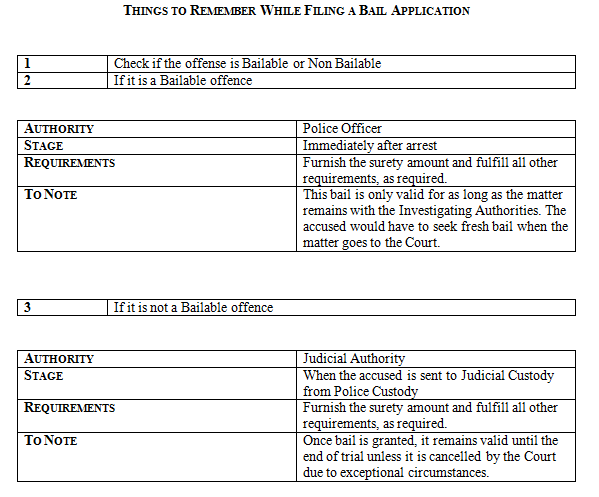

Though bail can be sought in either bailable or non-bailable offence, the authorities with the power to grant bail with respect to both are different.

What is a bailable offence?

A bailable offence as defined under Section 2 (a) of the CrPC is an offence which is shown as bailable in the first schedule attached to the CrPC or an offence which is made bailable by any other law for the time being in force.

A non-bailable offence is defined in Section 2(a) of the CrPC as any other offence apart from a bailable one. For example, murder under Section 302, dowry death under Section 304B, rape under Section 376 and attempt to murder under Section 307 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (“IPC”)

While this is not a blanket rule and there are always exceptions, it will be easy to determine whether an offence is bailable or not by looking at the years of imprisonment as punishment for that offence. A cap of 3 years or lesser than that usually means that the offence is bailable and anything above 3 years usually means that the offence is a non-bailable one.

When it comes to bailable offences, the Police has the power to grant bail after securing the surety amount but as soon as the challans are filed in Court, the accused has to fill the prescribed bail bond in order to get regular bail from the Court. For example, in India, a rather strange aspect of our criminal justice system is that bribing an election officer is considered as a bailable offence. In such a case, the person accused of bribing can secure bail from the police officer directly. Bail is a matter of right and the police officers are bound to let out the accused on bail if the guarantor, on the accused’s behalf, is present and the surety amount is furnished.

What is a non-bailable offence?

In a non-bailable offence, the Police does not have the power to grant bail. In these cases, the power to grant bail lies exclusively with the discretion of the judicial authority (i.e, the Courts)

An application for regular bail in case of a non-bailable offence can only be filed when the person is in judicial custody. Hence, the accused has to wait until the period of police custody expires and then apply for regular bail as soon as he is sent to judicial custody.

Anticipatory Bails

Anticipatory Bail is sought when the accused is apprehending arrest. The petitioner (prospective accused) moves an anticipatory bail application before the Court stating that s/he strongly apprehends arrest and seeks anticipatory bail – in anticipation of probable arrest.An Anticipatory Bail application can only be moved in the Sessions Court or in the High Court, the Magistrate’s Court does not have jurisdiction to entertain such an application.If the Anticipatory Bail application is rejected by the Sessions Court, the accused can then approach the High Court and thereafter, the Supreme Court.

What is Interim Bail?

Interim Bail is a relatively new concept that has emerged in criminal courts of late. It is an interim relief given by Courts before the anticipatory bail application is considered at length and decided. Interim Bail is a concept that is only applicable in case of anticipatory bails and is not applicable to regular bails, as in the case of regular bails, the accused is already in judicial custody. These interim reliefs are in the nature of directives issued to the Investigating Officer that in the event the accused is apprehended, that he be released or let out on bail.

The Courts can issue various directions in the nature of interim reliefs, the most common being an order stating that no coercive action be taken against the petitioner (prospective accused) while granting interim bail.

‘No coercive action’ implies that the accused would not be arrested, for instance, until the next date of hearing, when the status report (a report from the Investigating Officer detailing the current stage of investigation and the prosecution’s version with respect to the anticipatory bail application filed by the petitioner) would have been called for by the courts to assess the anticipatory bail application afresh on its merits.

Watch out for the second part of Bails and Anticipatory Bails where we discuss the Grounds for Grant and Refusal of Bail and the tricks of the trade involved in drafting the perfect anticipatory bail application.

About the Authors:

Advocate Shriya Maini is a young, bright, scholarly, advocate turned entrepreneur, currently practicing at the Supreme Court of India, the Delhi High Court and the District Courts at New Delhi. She specializes in dispute resolution and as an unabashed feminist, particularly enjoys criminal litigation. She is a graduate of Gujarat National Law University, India who then pursued the Bachelor of Civil Laws Programme on a full scholarship (Dr. Mrs Ambruti Salve Scholarship) sponsored by Dr. Harish Salve, Senior Advocate, from the University of Oxford, specializing in International Crime. As a recipient of the Oxford Global Justice Award 2015 for Public International Law, she assisted the President of the International Residual Mechanism for the Criminal Tribunals (MICT) at The Hague, Netherlands. She is now back in the Courts of New Delhi, India to pursue her passion in litigation. Additionally, she has recently been appointed as a Visiting Professor for International Criminal Law at National Law University, Delhi, India.

Advocate Shriya Maini is a young, bright, scholarly, advocate turned entrepreneur, currently practicing at the Supreme Court of India, the Delhi High Court and the District Courts at New Delhi. She specializes in dispute resolution and as an unabashed feminist, particularly enjoys criminal litigation. She is a graduate of Gujarat National Law University, India who then pursued the Bachelor of Civil Laws Programme on a full scholarship (Dr. Mrs Ambruti Salve Scholarship) sponsored by Dr. Harish Salve, Senior Advocate, from the University of Oxford, specializing in International Crime. As a recipient of the Oxford Global Justice Award 2015 for Public International Law, she assisted the President of the International Residual Mechanism for the Criminal Tribunals (MICT) at The Hague, Netherlands. She is now back in the Courts of New Delhi, India to pursue her passion in litigation. Additionally, she has recently been appointed as a Visiting Professor for International Criminal Law at National Law University, Delhi, India.

Ms Chethana Venkataraghavan graduated from GNLU in 2017. She is currently working as an Associate at Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas, Mumbai. She was part of the team that won Surana and Surana Corporate Law Moot Court Competition, 2013 and the Philip. C. Jessup International Moot Court Competition, India Rounds, 2016. She was adjudged the Best Speaker at the Finals of the Manfred Lachs Space Law Moot Court Competition, Asia Pacific Rounds, 2014. She is passionate about blogging and was involved in an initiative – Exam of Smile – aimed at reducing levels of stress and depression among law students across the country.

Ms Chethana Venkataraghavan graduated from GNLU in 2017. She is currently working as an Associate at Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas, Mumbai. She was part of the team that won Surana and Surana Corporate Law Moot Court Competition, 2013 and the Philip. C. Jessup International Moot Court Competition, India Rounds, 2016. She was adjudged the Best Speaker at the Finals of the Manfred Lachs Space Law Moot Court Competition, Asia Pacific Rounds, 2014. She is passionate about blogging and was involved in an initiative – Exam of Smile – aimed at reducing levels of stress and depression among law students across the country.

Comments

One response to “Bails and Anticipatory Bails: Part I”

[…] take off from where we left in the last post on Bails and Anticipatory Bails. Now that we know about Bails, Anticipatory Bails and […]