By Ishita Puri, St Xavier’s College, Mumbai.

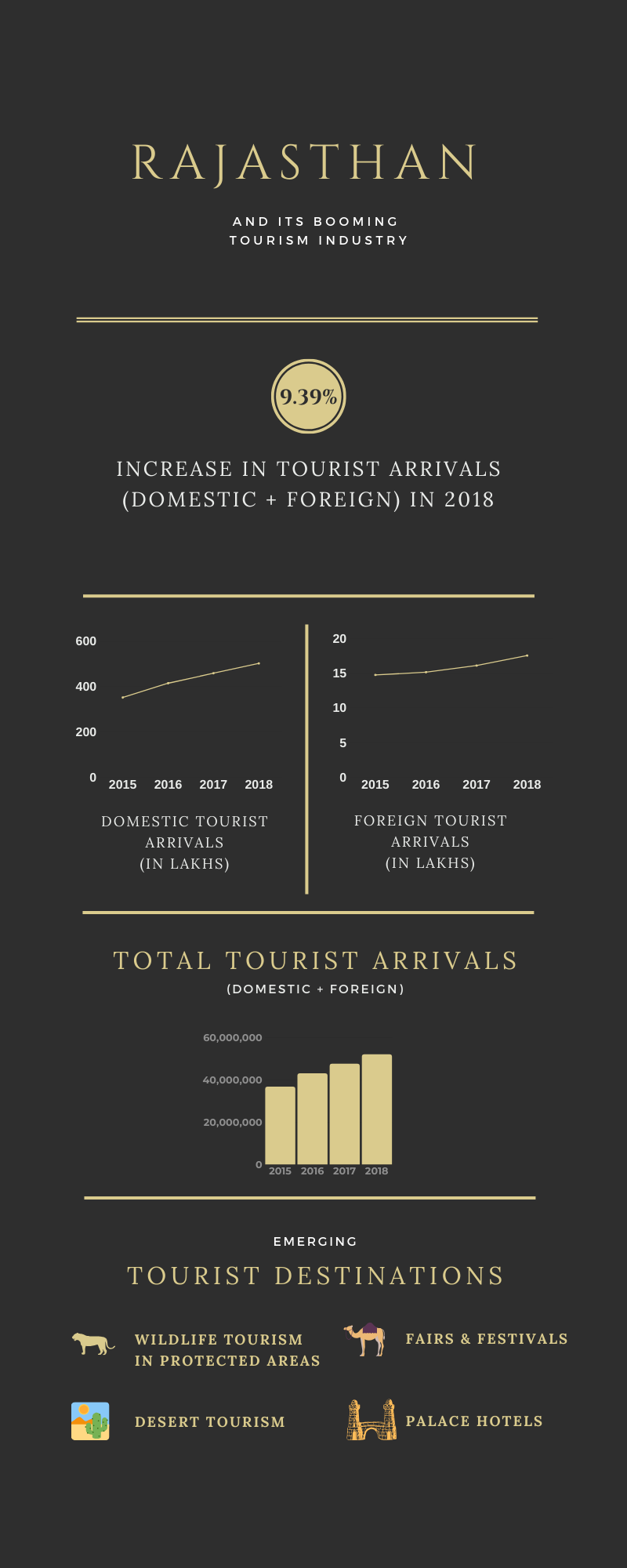

According to Lucy Long, “the basis of tourism is perception of otherness, of something being different from the usual.” In this sense, India does enjoy a vibrant and unique diversity of natural spaces – from the glaciers of the Himalayas to the backwaters of Kerala. Tourism is amongst the fastest growing sectors in the country and Rajasthan captures a major part of the industry with its lavish palaces, historic forts and deserts. In 2018, Rajasthan accounted for 2.7% of domestic tourist visits and 6.1% of the foreign tourist visits. Thus, a critique of the predicament of tourism on the ecology of Rajasthan becomes apposite to the discussion.

Who is the fairest of them all?

Fairs and festivals form an integral part of Rajasthan’s rich cultural heritage. It attracts tourists, both foreign and domestic, to its vibrant carnivals- having religious, sociocultural and economic significance. Organisation of fairs is linked to establishment of requisite infrastructure like hotels, airports, restaurants and recreational facilities to boost visitations. When uncontrolled, these activities put already-depleting natural resources of Rajasthan under tremendous pressure.

The growing fascination towards ‘ecotourism’, when applied to Rajasthan’s glorious flora and fauna, has corroborated the extension of this burden to even the protected areas. The sacred Pandupole Hanuman Temple, situated within the protected area of the Sariska Tiger Reserve, attracts lakhs of pilgrims each year. In this Pandupole Mela, special arrangements are made for the pilgrims inside for a fortnight, thus enjoying complete access to the resources. Their impact, often goes undocumented as the park remains open and the entry is made free for pilgrims twice a week. On these days even personal vehicles are permitted to go 20 kms within the forest that has repeatedly led to congestion and excessive emissions.

This is one of innumerable cases where endorsing tourism has superseded survival needs of the environment, despite the provisions of protected areas. Even the livestock fairs of Rajasthan, of which the Pushkar Camel Fair is one of the most famous, have become breeding grounds for illegal trade of camels, resulting in their diminishing population. Consequently, the Raika (hereditary herders), unwilling to sell their camels for slaughter, are now unable to sustain them.

Fortifying Heritage for Tourism:

Rajasthan, with its rich historic heritage in the form of forts, has charmed travellers who wish to go back in time and get the authentic experience of royalty. Though, with an influx of tourists coming to various cities and forest reserves and parks of Rajasthan, carbon emissions have also increased. Growing number of tourist vehicles on roads has led to a rise in pollution levels across cities in Rajasthan. Pollution particles, when settling on the fort walls, alters forts’ appearance drastically. The Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981 gives little powers to the State Pollution Control Board when it comes to enforcing punishment to violators of environmental guidelines. It empowers them to initiate the process and temporarily close the institution. The punishments, though, can be imposed only by a court of law.

Today innumerable forts in Rajasthan are plagued by this peril. The Chittor Fort is surrounded by cement factories and due to indiscriminate mining and quarrying activities, it is gradually losing its lustre. The 863 years old Jaisalmer Fort also faces a similar predicament due to untreated liquid wastes seeping through the fort walls. As the areas within have no proper plan for sewage treatment and disposal, the amount of water waste generated is accentuated by growing water needs of tourism.

Water and Wildlife in the Desert:

Foreign tourists in Rajasthan, bring with them an increased demand for water to counter the dry and hot climate of the Thar. Not only is the water resource depleting all over the world, it is far more critical reality in the drought-prone desert State of Rajasthan.

This strain is supplemented by the private tour operators who use alarming quantities of natural resources for construction of hospitality facilities. Udaipur, one of the major tourist destinations famous for its lakes, suffered the consequences of commercial exploitation of the environment. In 1997, the State government declared no construction zones around lakes and banned any construction within 200 meters of the High Flood Level. However, in the year 2000, this order was rephrased to allow construction in “the rare exceptional case”. Thereafter, an island on the Udaisagar lake was allotted for the construction of a sprawling five star hotel, but what remains unclear is the status of a concrete plan for the treatment of waste generated by a structure that stands in the middle of a water body. This puts the water at high risk of contamination, while also adversely affecting the flora and fauna in and around the island, even as some of these are guaranteed protection under the Wildlife (Protection) Act.

The government’s intention to support commercialised tourism activities at the cost of the State’s environmental policies is a serious cause of concern.

Unfortunately, this is not a standalone incident. In December, 2002, the then forest secretary issued guidelines to curb the increasing commercial encroachments in and around Ranthambore National Park. The said guidelines stipulated to ban all construction activities in this zone within 500 metres of the park boundary.

However, the tourism-lobby groups ensured that this direction was relaxed to allow construction of ongoing hotel projects under special categories. Today, at least fifteen hotels are based extremely close to the borders of the Park, which does not bode well human-wildlife interactions, outside the reserved area.

With the Supreme Court’s order to review Wildlife Tourism Guidelines in 2015, Rajasthan revised the same to permit tourism in core tiger settlement areas and in areas where the locals were relocated for the sake of environmental protection. This plan became a cause of concern due to its ambiguous treatment of existing hotels and commercial tourist activities.

However, increasingly, environmentalists in Rajasthan have taken up the route of legal activism, by filing RTIs and petitions with the National Green Tribunal (NGT), against environmental damage of the tourism industry. For instance: In 2016, the NGT stayed the Mount Abu Master Plan 2030 that intended to cut forests in the eco-sensitive Mount Abu zone, for commercial purposes, to accommodate the growing space demands of people – both locals and tourists.

Need for Responsible Tourism:

Rajasthan, with its abundant forts, mesmerising desserts and vibrant fairs and pilgrimages, poses as the perfect stop for national and international tourists. Additionally, the wide diversity of wildlife in Rajasthan’s protected areas – National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries – entices nature lovers from all over the world. Its desert ecosystem, harbouring a large variety of wildlife, has also transformed into major tourist destinations due to growing support for ecotourism. But true success of ecotourism activities is impossible without compliance of all the three subsystems – economic political and sociocultural – to the goals of conservation.

However, permissible use of motorised vehicles for tourism inside several reserved areas of Rajasthan has detrimental impact on the endangered flora and fauna that get disturbed. Unrecorded or unregulated access to national parks such as Sariska and Ranthambore, respectively, has shown adverse effects on the conservation projects. As demand of tourists to see tigers is repeatedly prioritised over safety needs of the environment, traffic of vehicles within the parks has increased. In Ranthambore National Park, crowding of tourist jeeps has caused considerable damage to the tigresses and cubs, pushing them to less protected areas outside.

Additionally, local people are the worst affected by the ill conceived conservation plans of private tour operators. Evicted from their homes either by force or by false hopes of an improved agricultural land, they are paid insufficient compensations that do nothing to restore their financial stability. For instance, villagers of the Umri village (inside Sariska Tiger Reserve) were relocated for better conservation of the protected area. However, their traditional rights over forest resources have not been fully recognised and compensated for as some of them have not received reimbursements yet. Similarly, the Raikas have challenged forest department over their right to use grazing lands near Kumbhalgarh Wildlife Sanctuary.

Restoring the synergy between conservation, tourism and survival:

For tourism to flourish in Rajasthan, conservation of the environment on which it is sustained, is very essential. Not only are these places rich in sociocultural and economic heritage, but also hold vital positions in conservation projects all over the country. The following measures can be adopted to strive for such an equilibrium between conservation and tourism:

- Establishment of secure association and partnership between various stakeholders would enhance the implementation of environmental guidelines, reduce incongruity among regions, through information symmetry and policy regulations.

- Reforestation of the barren hills must be undertaken as an attempt to recover and regenerate the lost biodiversity in desert ecology of Rajasthan.

- The government can set up ‘untshalas’ for the camels rescued from smuggling attempts and for the camels of Raikas who can no longer provide for them. This helps in avoiding involuntary neglect and starvation of camels due to lack of funds.

- State can combine the traditional knowledge of Raika with the avenues they possess for a better implementation of actions to conserve camels, whose population has fallen drastically in the last few decades. Benefits of such a tie-up are twofold: Firstly, this would act as a potential source of income for them, thus enabling them to fulfil their basic requirements at the very least. Secondly, this may also ensure that the state-drafted policies are effective as the Raikas bring in their traditional knowledge.

- Visitor management mechanisms like zoning and channeling must be used to pinpoint regions that are more suitable for higher use levels (lesser, uncontrolled interaction between humans and wildlife)

- Sustainable tourism plan must be formulated for each park and sanctuary in the state, which should be incorporated in the general park governance.

- It is of utmost importance to accurately measure encroachments in the entire regions and land-use plans must be developed and implemented, keeping in consideration the local people and the conservation efforts. Such plans must also be revised, from time to time, to ensure effectiveness of the conservation plans at the grassroots.

- Hotels must pay cess to the forest department, per tourist who visits the park. This can be done to ensure that revenue generated by the tigers must be partly utilised for their betterment and protection.

The bottom line is that tourism is a luxury that some enjoy, but an adequate and safe living space is a necessity for the environment and people who depend on it. Rajasthan possesses the potential and avenues for a responsible tourism circuit, emphasizing upon conservation aims and uplifting the local communities in the process. Sensitizing the tourists towards the fragile ecosystems and presence of watch guards to ensure that it remains responsible to its stakeholders – from animals to tourists- is the way forward. The role played by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) and civil society organisations is enormous in keeping a check on the growing commercial tourism activities and ensuring that the guidelines are followed diligently. The popular saying of “Atithi Devo Bhava” must not be restricted to just “Atithi” i.e. guests (tourists in this case), but must also include the environment that brings in tourists, in treating them as gods.