By Shalvi Singh, WBNUJS, Kolkata.

The Right to Information Act (RTI) came into force on 12th October, 2005. It replaced the erstwhile Freedom of Information Act, 2002. The Act was passed to “set out the practical regime of right to information for citizens in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority.” It applies to all States and Union Territories of India except Jammu & Kashmir (where J&K Right to Information Act is in force).

The Act covers all the constitutional authorities, including the executive, the legislature and the judiciary and also any institution or body established or constituted by an act of Parliament or State Legislature. The Central Information Commission (CIC) consisting of a Chief Information Commissioner and Information Commissioners not exceeding 10 has been given the authority to interpret the RTI Act, 2005.

RTI is a facet of Freedom of Speech and Expression as contained in Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India and is thus unquestionably a Fundamental Right. At the International level, RTI and its aspects find articulation as a human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In the past 10 years, the RTI Act has managed to give rise to a silent citizen’s movement for government accountability across the country. According to the RTI Assessment and Advocacy Group (RAAG), on an average, 4-5 million applications are filed under the Act every year. With these figures, the RTI Act is the most extensively used transparency legislation globally.

ELUDING THE RTI NET

It has been observed that the public authorities try to escape from the domain of RTI Act in order to protect their interests. In 2013, the six national political parties were held to be public authorities under the RTI Act. In a rare show of alliance they came together to condemn the order of the Central Information Commission and collectively refused to comply with it. They also moved an amendment bill in Parliament to exempt themselves from its ambit but fortunately, they did not succeed.

Several circulars have been issued by the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), a department for RTI which works under Prime Minister, since June last year. These circulars include, a format for giving information to applicants, harmonising the RTI (Fee and Cost) Rules and Appeal Procedure Rules under RTI Act, implementation of suo motu disclosure under S. 4 of the RTI Act and the uploading of RTI replies on the respective website of ministry or department. While the DoPT has issued regular circulars in favour of RTI, departments find ways to thwart it. The most misused sections of the RTI Act by the public authorities are S. 6(3) and S. 7(9). S. 6(3) says that if a public authority receives a request for information which is held by another public authority, “the public authority, to which such an application is made, shall transfer the application or such part of it as may be appropriate to that other public authority…” S. 7(9) states that, “an information shall ordinarily be provided in the form in which it is sought unless it would disproportionately divert the resources of the public authority or would be detrimental to the safety or preservation of the record in question…” Some authorities evade the responsibility by using S. 6(3) without going through their own records and they often cite S. 7(9) for denial of information.

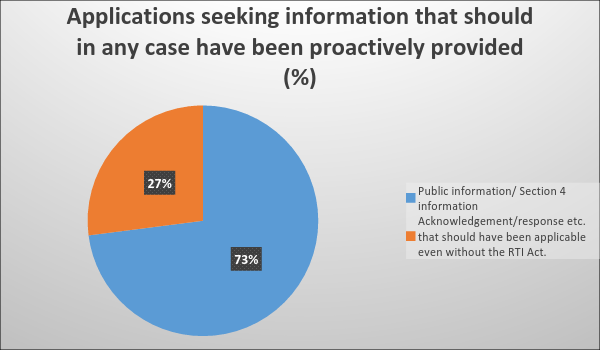

The officials also use the excuse that the large number of RTI applications being filed every year hampers the work process of the department as most of the time goes in addressing the applications. They often cite the remark given by Justice R.V. Raveendran in Central Board of Secondary Education v. Aditya Bandopadhyay, where it was said that “the nation does not want a scenario where 75 percent of the staff of public authorities spends 75 percent of their time in collecting and furnishing information to applicants instead of discharging their regular duties. The threat of penalties under the RTI Act and the pressure of the authorities under the RTI Act should not lead to employees of public authorities prioritising information furnishing at the cost of their normal and regular duties.” In contrast to this, it has been observed that out of the 4 million applications being filed every year about 3 million applications were such which sought information that should have been provided to them even without filing a RTI application. In light of this, the excuses given by the government that RTI Act is slowing down their work seems hollow.

INFORMATION BEING SOUGHT UNDER THE RTI ACT

In its report titled ‘Who uses the Right to Information Act in India, and for what?’, RAAG has mentioned the various reasons for using the RTI Act. According to the report, 43% of the RTI applications sought information relating to decisions taken for one or more of the entities for which information was asked. Apart from the information exempted under S. 8(1) of the RTI Act, decisions taken by public authorities are put out into the public domain. Therefore, the fact that such a large number of RTI applications are filed for enquiring about the details of decisions suggests that the government is not being able to effectively disseminate information about the decisions it takes. Not only does S. 4(1)(c) of the RTI Act obligate each public authority to proactively “publish all relevant facts while formulating important policies or announcing the decisions which affect public”, but in any case the communication of the details of a decision to those who are affected by it is an essential part of governance. The report also points out that a whopping 33% of the RTI applications sought to know what action had been taken or was proposed to be taken by a public authority on some matter that required action. It is not only important to communicate the decisions taken by a public authority to the affected persons but also to inform about what action was taken or is proposed to be taken about complaints made to the public authority. Given the large number of people who are using the RTI Act to find out the status and possibility of government action, indicates that this information is not being effectively communicated to the people. Furthermore, the report also states that 21% of the applicants sought information on financial matters. There were an equal number of queries from both rural and urban areas about past expenditure, apparently made to gauge its appropriateness and legitimacy. In addition to this, 20% applications were made to gain information about enquiries, investigations and assessments related to police cases/court cases and environment impact. This once again points out that the public authorities are not performing their duty of keeping the people updated about the progress (or the lack of it) about the investigations and assessments being done. Though there are certain cases where the RTI Act is being used as a tool for blackmail or for settling personal scores, these are negligible in number.

DILUTED LAWS

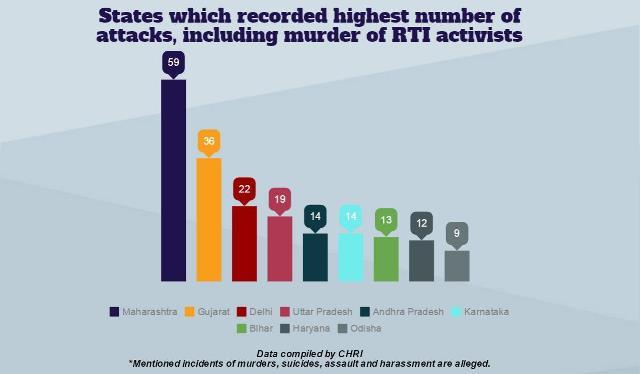

With reports of nearly forty RTI activists being killed, it becomes necessary to have supplementary laws such as whistleblower protection laws. These laws protect the activists who demand crucial information, having the potential to expose corruption within the government, in public interest. However, the Whistleblowers Protection (Amendment) Bill 2015, as passed by the Lok Sabha on 13th May 2015 to amend the Whistleblowers Protection Act 2014, has renewed concerns as it makes the information seekers liable to be prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act. Thus, instead of providing them immunity, the amendment makes their position vulnerable. Furthermore, the Bill completely dilutes the provisions of the earlier law removing everything exempted under S. 8 (1) of the RTI Act from the ambit of whistle-blowing.

NEED FOR PROPER IMPLEMENTATION

The success of any law depends on its efficient implementation which in turn depends on the awareness levels among the citizens. The low level of awareness among the people about the RTI Act is exemplified by the data collected by RAAG in the year 2013. According to the report, less than 35% people in the rural areas and about 40% people in the urban areas are aware of the RTI Act. Such perturbing figures illustrate the need of educating people about the importance of the RTI Act. It is also to be ensured that the public authorities perform their duties sincerely. In a democratic country like ours, the free flow of information is a must as it helps the society to grow. Freedom of information brings transparency in the state affairs and makes the government more accountable. Thus, unless the effective implementation of RTI Act is done, RTI still has miles to go.