Coronavirus outbreak and the consequent nationwide lockdown has impacted nearly 40 million internal migrants, as per the World Bank, because of the uncertainty of their living conditions and their excludability in any specific demographic. The current pandemic saw an exodus of migrant workers, which made everybody unsure of the actual number of people who work in the informal economy. More than 90-92% of the workforce in India is informal, which directly means that they have no social and employment security.

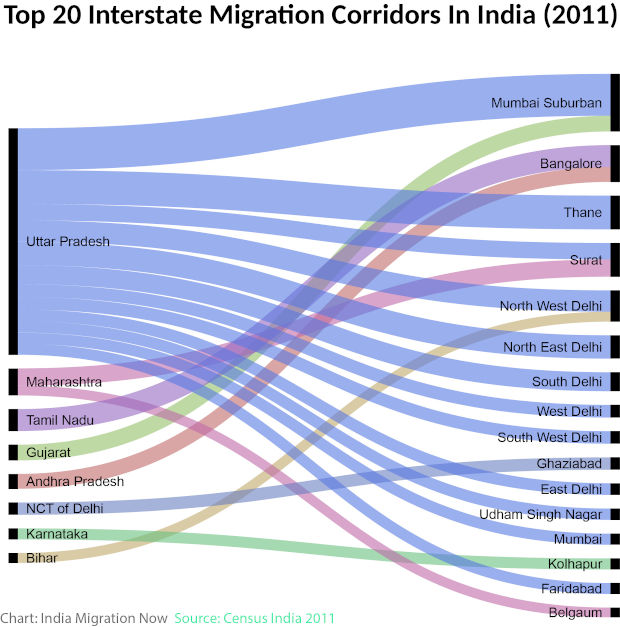

According to Census 2011, there were a total of 139 million interstate migrants. This number is not just limited to people migrating in search of employment, but ranges from education to marriage. The data confirms that the maximum number of interstate migrants are from the States of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, which account for 20.9 million people. But, there is still no exact estimation on how reliable these figures are, as the available data does not take into account circular or short term migrants. Without any real time estimate of data on migrant workers, it becomes difficult for the government to make policies and direct their resources to address their needs. This quandary has been witnessed more strongly when it came to extending COVID relief packages to migrant labour and assessing the outreach of our social security policies for the informal sector during times of an emergency.

Social Security Benefits Subject to Data

According to the International Labor Organization, there are around 20 to 90 million domestic workers in India, most of whom fall in the category of migrants. The Periodic Labor Force Survey conducted in 2017 by the National Sample Survey Office of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation estimated that there is around 1.5 crore workforce with jobs of the vulnerable category. Migrant workers numbered at 81 lakhs amongst this section of workers.

The Unorganized Workers Social Security Act 2008 which aims to prepare welfare schemes periodically for unorganized workers, lacks clarity in defining unorganized workers in organized sectors. It excludes a vast section of unorganized workers, with only 5-6% enrolled for its benefits. It does not even penalize authorities who fail to register such workers. Considering that domestic workers fall in the category of unorganized sector labour, the lack of a reliable number of migrants employed as domestic help would mean that their social security needs remain unfulfilled for want of authentic data. Even in the recent Social Security Bill 2019, important areas like provident fund and employment benefits are left at State’s discretion, whereas in December 2016, Centre admitted that many States do not have data on the numbers of migrant workers. Similarly Code on Wages 2019, created to simplify the complexity of India’s labor laws into four codes, only takes into consideration establishments with more than 20 workers, which means it automatically excludes a large section of informal workers and migrants who are employed in unaccounted for means of employment.

The ineffectiveness of the Inter-State Migrant Workers Act, 1979, to regulate employment and matters connected with inter-state migrant workers is also notable. The Act requires to maintain a register of all the interstate migrant workers. The inability of every State to do so has resulted in an abysmal lack of data on migrant workers. The inaccurate registrations at the initial level has paved the way for failure of other associated policies, which also require data on migrant workers. Such provisions include Minimum Wages Act, Equal Remuneration Act, Contract labor (Regulation and Abolition) Act, and Building and other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1996. As per the Registrar General of India, there is a high possibility that data used by all such policies are more than fifteen years old, as digital generation of migration data is time consuming.

Researchers argue that there are large variances between macro data and micro studies data, which further creates complication in effective policy making for the migrant population in the informal sector of the economy.

Status of COVID-19 Relief Policies in Absence of Data

The data crisis got more attention when the Finance Ministry’s recent relief package of Rs. 20,000 crores, was extended to support stranded migrants due to the COVID-19 lockdown. In her announcement, the Finance Minister stated that the estimation of such migrants stands at 80 million. This number is already twice as estimated by the Census for economic migrants. Even after the first Coronavirus relief package, the country witnessed a huge number of stranded workers in need for relief and social security. The government also acknowledged that their efforts to extend services to stranded migrant workers has been obstructed by lack of extensive and reliable data on the size of migrant workers.

The financial struggle of migrants during the COVID pandemic reflects the critical need for appropriate data, before services and schemes can be extended to the most vulnerable class of India’s population. As shocking as the COVID pandemic, is the lack of relevant data on circular migrant workers in the country. There exists no information about their hometown and workplaces with any of the States or the Central government.

Without any statistical account of their actual numbers or knowing the nature of their mobility, it is difficult for any State to formulate policies for them. Official registers underestimate the exact number of short term migrant workers, which is true for all of seasonal migration in the country. Recent field studies have shown that informal data is the only record for the majority of the migratory movements for employment in India. There is a sharp increase in migration since 2011, and Census being a ‘stock’ form of data, taken every ten years, fails to reflect or measure the correct numbers which are required for extending social security schemes, specially in unprecedented times such as now.

The COVID relief policy also intends to cover individuals who are not registered as beneficiaries of the National Food Security Act, 2013 for distribution of ration. The Centre will spend a total of Rs. 3500 crores for this, and expects that around 8 crore migrants will benefit from the same. However, lack of data has made the authorities uncertain about their allocation programmes and States are expected to keep a check on how these are implemented and distributed. There is a high probability that many unregistered workers will remain uncovered. There is a chance of migrants being registered at their place of residence and hence rendered ineligible to receive this relief package at the place of migration because the records will reflect that they are already registered under the NFSA. This shows poor forethought in the present policy when in fact the authorities are well aware of the lack of clear records of registrations in States under the NFSA, 2013. It has been estimated that around 10 crore people have not been included in National Food Security Act coverage due to their population growth since Census 2011, which also suggests that COVID relief package might even fail to cover this shortfall.

The lack of cooperation among Centre and States because of vagueness of data at both levels has resulted in the invisibility of migrant workforce. While governments at both levels have provided registration portals for stranded workers, there is lack of clarity among them given the tedious registration process. The Labor Commission has claimed that they do not have State and district level data on migrants, despite the direction to address the concerns of stranded workers. Even if data is available, the way it is collected, cannot reflect the exact number of migrant workers in this pool.

Need for Policy Overhaul

- Since welfare schemes by the government during an emergency, cannot directly reach the targeted population because of lack of appropriate data, it is necessary that an on ground network is developed, which ensures proper registration of migrant workforce at their workplace and periodic checks by local governing bodies, so that their issues can be addressed at a more local level in the absence of large scale data.

- Most of the migrants do not have ration cards or any proof of citizenship, so this requirement should be nullified largely for the extension of social security benefits. There should be authorities to especially keep a check on the distribution system in such cases, where the challenge is to ensure that unregistered beneficiaries get access to social security schemes.

- In the absence of authentic and reliable data from official statistics, the government should collaborate with regional NGOs, academic and industry researchers. This can lead to collection of data from a larger section. Additionally there is an urgent need for better cooperation between the Centre and States with regard to sharing a reliable record of migrant workers.

- Central & State governments need to share and manage their respective data on outgoing and incoming migrant labour population. This can ensure that duplication of data or logistical roadblocks for extending social security benefits can be avoided.

- There is also an urgent need to collate data in the highly employable sector of household level services. This can be done by recording the number of households receiving such services in a particular area and data localisation for collating records of workers therein.

It’s evident that without authentic estimates, it is not easy for government policies to benefit the underserved citizens. There will be a huge lack of resources or a waste of them, neither of which will serve the goal of addressing the needs of the migrant population. In times when an economic crisis looms large, extending social security schemes should not only aim at providing economic stability, but should go beyond that to encourage social inclusion and safety from any kind of harassment, but the starting point for all of this will be availability of reliable data.

By Himadri Tripathi, Research Associate, Policy